Qin Feng: The Movement of Qi

Achille Bonito Oliva (Curator; Critic; Founder of Trans avant-garde Movement) pointed out:Qin Feng‘s research therefore, goes beyond all permanence within his own cultural territory, experiencing a dialectic relationship with the artistic production of other countries. Between Tao and Zen, vertigo and calmness, vertical and horizontal, Qin Feng’s abstraction ruptures the vision of Western perspective that imposes a single point of view, opening up instead to a multiple vision which is in eternal movement.

Because the Chinese vision is based upon the circular Tai Ji symbol which has no beginning and no end, developing an image of the world that is spiritual and without hierarchies. While the Western viewer looks at a painting from a single point of view, there is no doubt that an ancient or modern Chinese reader opening a scroll of paintings will look at it as he walks. This is the art of Qin Feng, an art in joyful movement.

Eastover Estate & Eco-Village in Lenox Mass. will be home to the dynamic art of Qin Feng, a leading contemporary ink painter of the Chinese avant-garde, whose intensely emotional and explosive works speak to new generations in both China and the West, without jettisoning their link with traditional Chinese brush-painting. His work has been exhibited at institutions around the world, including the Museum of Contemporary Art, Beijing; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Israel Museum, Jerusalem; Saatchi Gallery, London; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; and the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

A master of coalescence, Qin Feng seamlessly blends together the centuries-old art of Chinese ink painting and the modern concepts of the Abstract Expressionists in arresting series of meditative images. Bold brushstrokes, ethereal trails and plays on positive and negative space take his images beyond their aesthetic beauty to represent delicate balances, such as that of nature and man. Embodied with motion and representations of time, his pieces poetically combine Western gestures and Chinese Calligraphy. His artworks are both culturally resplendent, as well as modern marvels of contemporary art.

Following his studies at Shandong University of Art and Design, Qin moved to Berlin where he began to fuse Western modernism and the Chinese ink tradition, using traditional calligraphic materials but employing his brush with the unrestrained energy of the Abstract Expressionists. His use of tea, which represents the East, and coffee, the West, in the backgrounds of his ink paintings, emphasizes cultural contrasts and his attempt to bring the two together.

Qin’s upbringing in Xinjiang, located in the extreme northwest of China, profoundly influences his work. Once an intersection for Silk Road trade routes, Xinjiang historically has been a center for multicultural and multiethnic coexistence. This legacy continues today, making Xinjiang a unique locus for different languages including Chinese, Arabic, Uighur, and Hindu. Qin’s childhood in Xinjiang, and later his travels abroad, exposed him to varying cultures and languages, resulting in his present fascination with written and spoken word, systems of universal communication, and cultural difference. His work of the last decade often explores the theme of the ‘origins’ of civilization and incorporates autobiographical reflections, including his childhood memories of watching the physical torture and suffering of his parents during the Cultural Revolution (1966–76).

His vision of a globalized world where influences between East and West are reciprocal is part of a long tradition. Zen has influenced American action-painting, European painting and the music of John Cage. American pop art has stimulated Chinese figurative work in its representation of urban reality. But overall Qin’s vision is anti-rhetorical, inclined to restore an interior and mental human condition. For this reason it rejects the fixed Renaissance perspective. Here the vision is anti-perspective: his abstract painting looks at the world from different angles with a gaze always in movement which creates dynamic images.

Yet in spite of its anti-perspectivism, Qin’s art remains true to the profound Chinese vision of the circular Taiji symbol, which has no beginning and no end, developing an image of the world that is spiritual and without hierarchies. While the Western viewer looks at a painting from a single point of view, there is no doubt that an ancient or modern Chinese reader opening a scroll of paintings will look at it as he walks. This is the art of Qin Feng, an art in joyful movement.

Review of Qin Feng’s Art

“The power of Qin Feng art comes from the thorough communication with rich ancient civilization and from the unrest burst of primitive impulse. If ancient civilization could blur us in the brightness of the sun, primitive impulse would drench us in the spirits….Qin Feng is good at assimilating the power of ancient civilization and primitive impulse, thus rendering his works hallucinating.” Peng Feng, in Artintern.

Qin Feng on “What do you see?”

“What are you looking for? What do you see? You see what you want. You want what you see. And then the scenery ends up being what you perceive. There are multiple angles. It’s like a glass of water. If I turn it over and it doesn’t spill you would ask ‘Why is water still in it? It is supposed to spill.’ You are not bound by those laws of physics with this type of [abstract] art. But with a glass of water, even if you spill it, it is not the end of the world. You just have a water puddle.

My art is really aligned with my philosophies, rather than a purely pictorial depiction of real life. If you spin the work 360 degrees, it will just look different at different angles; you might see different things a little. You stare at this one object standing up or sitting down for your whole life and then all of the sudden one day you lie on your side and you think, ‘Oh, I’ve never seen this before.’

There were these kids who once came up to me and looked at one of these paintings and said: ‘Is this new, I really like it.’ And I said ‘That is the same piece you saw before’ and I realized I had flipped the orientation. Then every time I would turn it, the kids would say ‘Oh, it is so much better than the last time! It is totally different from the last time.’ But by the fourth time I had turned it 90 degrees, we went back to square one and the kids would say ‘Oh, I’ve seen this before! But I can’t put a finger on it though.’”

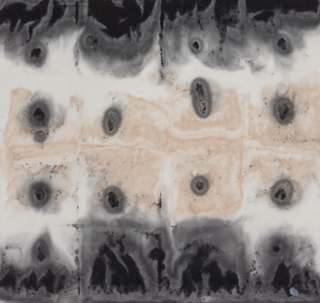

LI GANG: SEQUENCE VARIATION – Contemporary Ink Art Exhibition

Li Gang’s attitude towards art is nothing short of distinctive. His art hints at a “relax” attitude that seems to have run through the start of his journey in experimental ink to present, as well as a growing sense of “non-action”. In facing the tangibly taxing subject of contemporary art with the concept of “non-action”, the artist’s strategy equates that of giving a double negative answer. Li’s personality and temperament underline his work. “Non-action” does not refer to the absence of action. Through his reflection on the nature and value of art, his experiment of ink has entered an abstract state to an extent from the start. In the same vein as Western abstract drawing, his work seeks to build a universe of painting outside of the world of tangible images, giving an “autonomous existence” to painting.

It is difficult to execute such ideas in ink, since the form of painting carries inherently abstract attributes. However, the form is not entirely abstract, since the expression of its attributes relies on external subjects. There is infinite room to this tradition of “realm”, which lies at the heart of the difficulty of experimental ink. Li’s “relax” approach lies in his transcendence of the form of ink to reach its structure; it stems from his excluding of the limits and interference imposed on expression by tangible imagery, as the artist reaches the realm of “intangibility” and “non-imagery”. Yet his “non-imagery” is not the abandonment of imagery, but the composition of images with imaginary strokes that have no association with or allusion to reality.

In his work are various orders that are self-contained, and these structures are often referred to as the “elements of ink”. In my view, these “elements” are not isolated entities but form a coherent whole in the painting like in a DNA sequence. The birth of these elements is largely spontaneous and random, and yet it has its own organic order. In this context, we can see that Li’s work stems from the same concept as those purely abstract paintings, as the artist transforms one’s feelings of the secular world into orders of painting. These orders belong to a mental realm where Li contemplates and where the self-contained structures of his work are born. To an extent, the success of experimental ink lies in the transformation of concept. However, the transcendence of ink and brush remains the essential question for all forms of experimentation, considering the long-established attributes of ink as a medium. The answer is tied to the transcendence of the formula of traditional ink and brush, which creates a new manifestation of the art form that echoes its evolving structure and concept.

In this regard, Li’s work is ground-breaking. If he conveys a “relax” cultural attitude in the expression of his concept, he totally “lets go” of the execution of form and craft. He discards the traditional brush for objects that can be made use to leave traces of ink, blending the imprints of objects and drips, turning “painting” into “structure” to create a new and purer quality for the creative language. The repetitive imprints are symbols of the mind.

In gauging an artist’s work, one must examine whether it manifests an inherent uniformity and formal expression in its concept and language. Li’s art preserves the purity of painting and builds a unique order of the mind, while featuring imprints of daily objects that carry attributes of real life. This combination shapes Li’s experience of ink, and shows the possibility of fusing the classical spirit and the randomness of daily life. On this level, his experiment demonstrates the key characteristics of contemporary art. His expression is set for infinite expansion in a rich artistic universe. (Dian Fan/ Critic,Curator)

Li Gang, born in Guangdong in 1962, works and lives in Beijing. From 2002 to 2017, he held about 15 solo exhibitions in major galleries in China, France, Germany and the United States, and 30 group exhibitions in museums, galleries and art institutions in China and around the world.

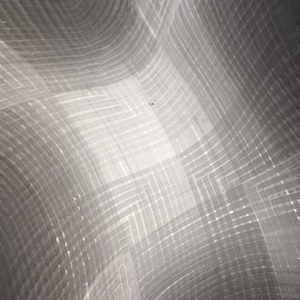

Zhang Zhaohui: The Essence of Light

At midcareer, Zhang Zhaohui is an artist fully equipped—both conceptually and technically—to infuse Chinese ink paining with selected elements of Western modernism, thus producing a hybrid form that revitalizes his culture’s single most representative medium. This creative dualism began with the painter’s education and has found its fullest expression in his art.

Born in 1965 in Hebei Province, Zhang was spared the ravages of the Cultural Revolution because of his family’s longstanding military service. Instead of undergoing deprivation or internal exile, he grew up in an army compound set amid the area’s famous Qing Dynasty palaces, temples, and gardens, where the precocious boy sometimes practiced traditional Chinese painting side by side with adult officers. His childhood dream was to become a literati-style artist and poet. Later, as an undergraduate, he majored in museum studies at Nankai University in Tianjin, where training centered on antiquities—the focus of virtually all institutional collections in China at that time.

During the great Opening Up of the 1980s, Zhang organized numerous talks, exhibitions, and events at his school. While maintaining his deep admiration for Chinese tradition, he also fervently wished to be up-to-date on such activities as Robert Rauschenberg’s galvanizing 1985 exhibition at the National Art Museum of China in Beijing, various postwar artistic and literary developments in the U.S. and Europe, and China’s own astonishing ’85 New Wave Movement, which spurred the creation of experimental art throughout the country.

Zhang graduated from college in 1988 and was hired as an assistant curator at the National Art Museum in Beijing (NAMOC). During his seven years there, he worked with many international galleries, museums, and foundations, thereby gaining a firsthand acquaintance with today’s global art system and helping to bring to China shows by such figures as Gilbert & George (Britain), Pierre Soulages (France), and Antoni Tàpies (Spain). Meanwhile, within China, artistic ferment continued in the massive “China/Avant-Garde” exhibition at NAMOC in 1989, the Yuanmingyuan and Beijing East Village artist neighborhoods, stylistic movements such as Cynical Realism and Political Pop, and collectives like the New Measurement Group in Beijing and the Big-Tail Elephant Group in Guangzhou.

Zhang’s position at NAMOC was in the folk art department, dealing with rural artifacts, so he was not directly involved in “China/Avant-Garde.” But he was witness to the entire event and deeply absorbed by the attendant colloquium and other debates. As a devotee and practitioner of ink painting, Zhang wrangled personally with the question of how China’s signature art form could be reconciled with the formal disruptions of contemporary art. His quest led him to obtain an MA in art history in 1992 from the Chinese National Academy of Arts, Beijing, a school known for its emphasis on traditional Chinese arts with an admixture of Western academic-style painting.

In 1995, Zhang traveled to the United States thanks to a grant from New York’s Asian Cultural Council. Soon he enrolled upstate at Bard College—a famed bastion of advanced art theory—in the program called Curatorial Studies in Contemporary Art. During the summer of 1997, Zhang served as an intern at the Asia Society in New York, where art historian Gao Minglu (formerly one of the chief organizers of “China/Avant-Garde”) was in the process of curating the landmark exhibition “Inside Out: New Chinese Art,” which presented experimental work from seventy-two individual artists and groups from mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. Asked by a skeptical fellow curator if he thought that examples of ink painting belonged in the show, Zhang argued for their inclusion, saying they represented a new stage, a new adaptation, of this ancient but constantly evolving medium. His increasingly fascination with the impact of Western modernism on Asia—particularly as manifest in the works of pioneering artists like Isamu Naguchi, Nam June Paik, and Lee Ufan—led Zhang to organize a 1998 Bard College master’s thesis exhibition titled “Where Heaven and Earth Meet: Xu Bing & Cai Guo-Qiang.”

Returning to China in 2000, Zhang studied in the graduate art history program at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing, for three years (2003-06), ultimately deciding to forgo a dissertation and a secure university teaching career in favor of pursuing his own art. Having made this bold decision, Zhang immediately began to experiment. He founded the Fingers group in the 798 art district in 2008 and produced such works as You & Me, an installation of two life-size male and female cookie-cutter-like metal forms. He used the figure outlines in photographs, shown in grids in the “Together” series, depicting visitors posing next to and inside the silhouettes—a comment on gender conformity and non-conformity, perhaps, and on the ubiquity of the bonds of family and friendship. Zhang also created reflective Metal Man and Mirror Man suits, which he wore in one-person walking performances. In this case, the self was “protected” like a knight inside his armor—or like an everyday citizen playing one of the conventional social roles reflected in the suits’ polished surfaces. In the manner of the Mudman (Kim Jones) who began appearing in the U.S. in the 1970s or Zhang Huan wearing a meat suit in his My New York performance in 2002, Zhang the artist remained secreted within his outwardly outlandish persona.

It soon became evident, however, that Zhang’s mind and heart were set on something more contemplative. He became convinced that traditional Chinese ink paining, in all its flexibility and formal variety, could be adapted to contemporary artistic concerns, both domestic and international, thus becoming a versatile contemporary technique that embraces the global, and the perpetually new, while continuing to honor its own cultural origins. In 2009, Zhang began producing the ink-and-wash drawings of the “Soul Mountain Series,” exquisite landscapes combining—in a dark, haunting fashion—the traditional Chinese elements of mountains, water, mist, and light. Yet there is also a hint of Edvard Munch in the oozing semi-abstraction of the interacting areas of earth and sky, in the modernist refusal to particularize trees, rocks, vegetation, dwellings, or human figures. Clearly it is the visual and emotional gestalt of each composition—the black mountains standing solid and stark against the luminous flux of more vaporous components (fog, water, light and shade)—that matters in these works, not any obeisance to literal representation. This interplay between the eternal structures of nature, the abiding physical counterpart of laws of cosmic order and harmony, with its ephemeral daily and hourly effects of weather, seasons, water flow, and life phases—this is essential theme of Chinese ink art, caught here from a dramatic contemporary perspective.

Over time, this reconciliation of apparent contraries—timelessness and immediacy, tradition and modernity—was capsulized for Zhang in the infinitely adaptable flow of the ink line itself. During a transitional phase, around 2011, he harnessed that flow of parallel lines, varying in weight and speed, to the presentation of lexical forms (for example, the hammer and sickle, the dollar sign), implicitly commenting on the way human consciousness—subject to ingrained psychology modalities and the limitations of language itself—tends to translate immense political and socioeconomic complexities into simple, easily manipulable signifiers: emblems that are iconic, fraught, almost oracular in their openness to conflicting and ever-changing interpretation.

Zhang soon eschewed that sign-language for pure linear abstraction. By 2012, he was working steadily in the style for which he is now widely known: patterns of black ink lines on paper—sometimes curving, sometimes rectilinear and crisscrossing—that evoke geometric forms and varied illumination as distantly, yet provocatively, as Agnes Martin’s grids evoke landscape. Some commentators (notably Clive Tzuang, professor emeritus, National Taiwan University, in his contribution to the symposium “Century of Light: Art and Science in the Work of Zhang Zhaohui” at Bennett Media Studio in New York in June 2018) have related these patterns to scientific experiments in optics and subatomic physics: the behavior or light waves or photons when subjected to filters. We can understand how this parallel might arise. All depiction, after all, is a study of light—how it pervades the atmosphere, how it strikes objects and reflects at various frequencies to our eyes. Zhang is an intuitive artist, not a research technician, but his long examination of art—and its ways of representing the world (or, more accurately, conditioning our perceptions, both retinal and cognitive, of the world)—has taken him into the heart of light itself.

For Western viewers, one of the most puzzling aspects of traditional Chinese painting is the preternatural evenness of its illumination. To eyes conditioned by the dramatic, raking shafts of Caravaggio and the soft volume-modeling interplay of radiance and shadow in Rembrandt and Vermeer, the uniformly “flat” luminosity of much Chinese painting can be disconcerting. And so it remains until one grasps two principles: first, that these ink-and-brush images seek to convey the spiritual essence rather than the natural appearance of their subjects; second, that this calm evenness of illumination echoes a larger sense of cosmic order, a belief in the transcendent harmony of life’s rhythms and cyclical changes, whether seasonal, historical, or personal.

Something like that traditional Chinese notion is manifest in the work of America’s nineteenth-century Luminist landscape painters and even in the light-drenched images of Europe’s Impressionists. Yet, in the West, there is always a countercurrent at work, because light is historically conceived by Euro-American thinkers as an active agent. In mythology, creation itself begins with the divine commandment “let there be light.” Later, brightness struggles with darkness—good against evil—in the Manichean philosophical schema. Dante, in the fourteenth century, equates light with God’s love, radiating outward through all the realms and levels of existence. The Illuminati regarded light as synonymous with wisdom. In optics, it is the sum of all colors, revealed to us through a prism. In cosmology, light’s speed is the upper limit of travel: nothing can exceed it. In biology, it animates not only plants, through photosynthesis, but virtually all organic life.

Perhaps nowhere is the hemispheric cultural divide clearer than in the contrast between the Eastern meditative goal of Enlightenment, a contemplation grasp of the oneness of all things, which stands in stark contradistinction, the West’s eighteenth-century Enlightenment, a collective purging of superstition, error, convention, and faith for the sake of a ceaseless inquiry, a driving empirical rationalism. The latter enterprise is dedicated, so the speak, to the truth of particulars, to facticity over poetry.

Zhang Zhaohui’s signature accomplishment is to bring all these varied, and often conflicting, associations together in solidly composed abstract works that have an eidetic effect on the viewer’s mind. Quantum physics and Song Dynasty landscapes, fleeting impressions and enduring substructures, the cosmological and the microscopic, nature’s linear changes and its cyclical stasis, diffuse illumination and focused, penetrating beams—all these and more are encompassed in Zhang’s art. This painter considers ink art a key contemporary mode of art-making. So what does he depict? Only infinity—and its minutest details.